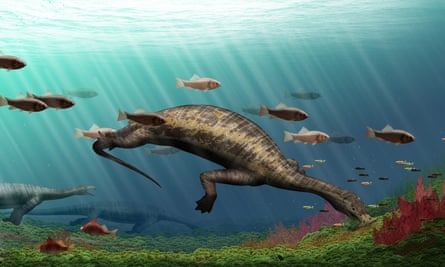

The body of Atopodentatus is fairly unremarkable in reconstructions. Other than the hammerhead face of the animal, its body is something we would consider rather typical for a swimming marine reptile. There are basic flippers on the forelimb and hindlimb; show here as early flippers with the digits extending just beyond the edges of the webbing. In appearance these flippers are not unlike the feet of ducks. They are less like the flippers we typically see in marine reptile reconstructions (plesiosaurs and ichtyhosaurs in particular) or in living marine reptiles (think of sea turtles). These flippers likely influence the evolution of the tail as well.

The tail of the animal is not paddle-like, and therefore probably not adapted for powered swimming. Considering the evolving flippers, that tail might not have been used in swimming at all. We could hypothesize that over time and evolution that the tail would become smaller (thinner, shorter, or any combination) like those of turtles or some of the plesiosaurs that we know. The tail would probably aid in turning a very small amount, if at all. However, it is unlikely that this algae grazing reptile needed to turn quickly in its daily life, so the tail not serving as a rudder or a propeller is not unexpected. I cannot speak to its overall speed, and I don't know if there is much study in that area either yet and saying that it likely didn't need to turn quickly is not an indictment of its overall traveling speed. I imagine, just as an off the cuff idea, that Atopodentatus was much closer to a manatee or a sea turtle than other animals in terms of its swimming speeds. That would allow for short bursts, but overall indicate a nice slow meandering through much of its daily life.

The body itself, in the image below, is fairly average sized. There are reconstructions that show Atopodentatus with a more manatee-like pot belly as well. This imagery meshes well with the increased size we see in many herbivorous animals. One of the reasons for that, many of us know, is the need for increased digestive organ space. In some animals that can include elongated intestinal tracts, multiple stomachs, or organs like gizzards or crops that serve pre-digestive roles and often contain rocks to help grind down plant matter. Could Atopodentatus have had any of these kinds of extra long intestines or accessory organs? It is certainly possible! We would likely need a mummified fossil to be entirely certain, but some of the better preservations of this animal may also have clues. Could those accessory organs then lead to increase abdominal sizes in Atopodentatus? It is likely that they could, and, as noted before, some interpretations of reconstructions have included enlarged abdomens. That idea has permeated to the toy industry as well, so be prepared for young scientists whose first interactions with Atopodentatus are with an elongate, hammerheaded, and pudgy marine reptile.

No comments:

Post a Comment